The HIV/AIDS crisis in the late 1990s brought access to medicines challenges to public attention, when millions of people in developing countries died from an illness for which medicines existed, but were not available or affordable.

Millions of people around the world do not have access to the medicines they need to treat disease or alleviate suffering.

The HIV/AIDS crisis in the late 1990s brought access to medicines challenges to public attention, when millions of people in developing countries died from an illness for which medicines existed, but were not available or affordable.

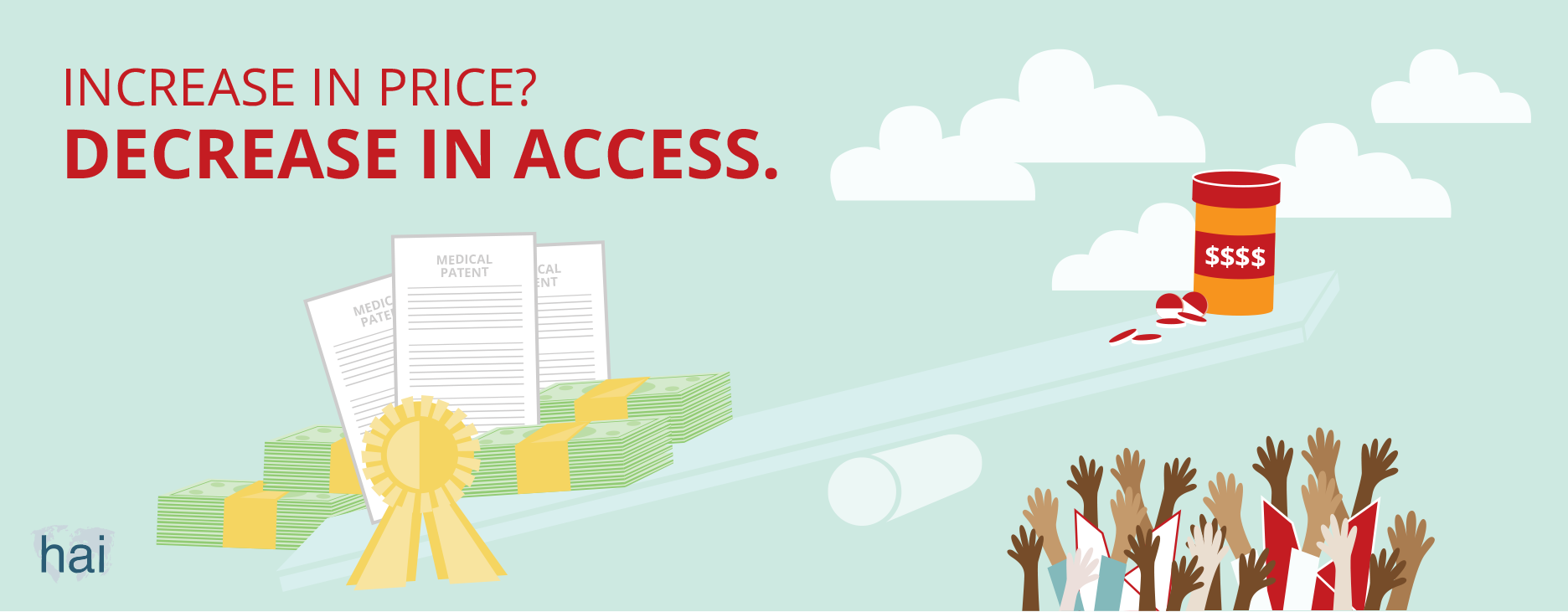

The high price of HIV/AIDS medicines focused attention on the relationship between patent protection and high medicine prices.

Today’s patent system is out of balance. It provides excessive rewards to patent holders while creating huge costs to society. Those who cannot afford to pay for newly-innovated medicines are excluded from the benefits these medicines bring.

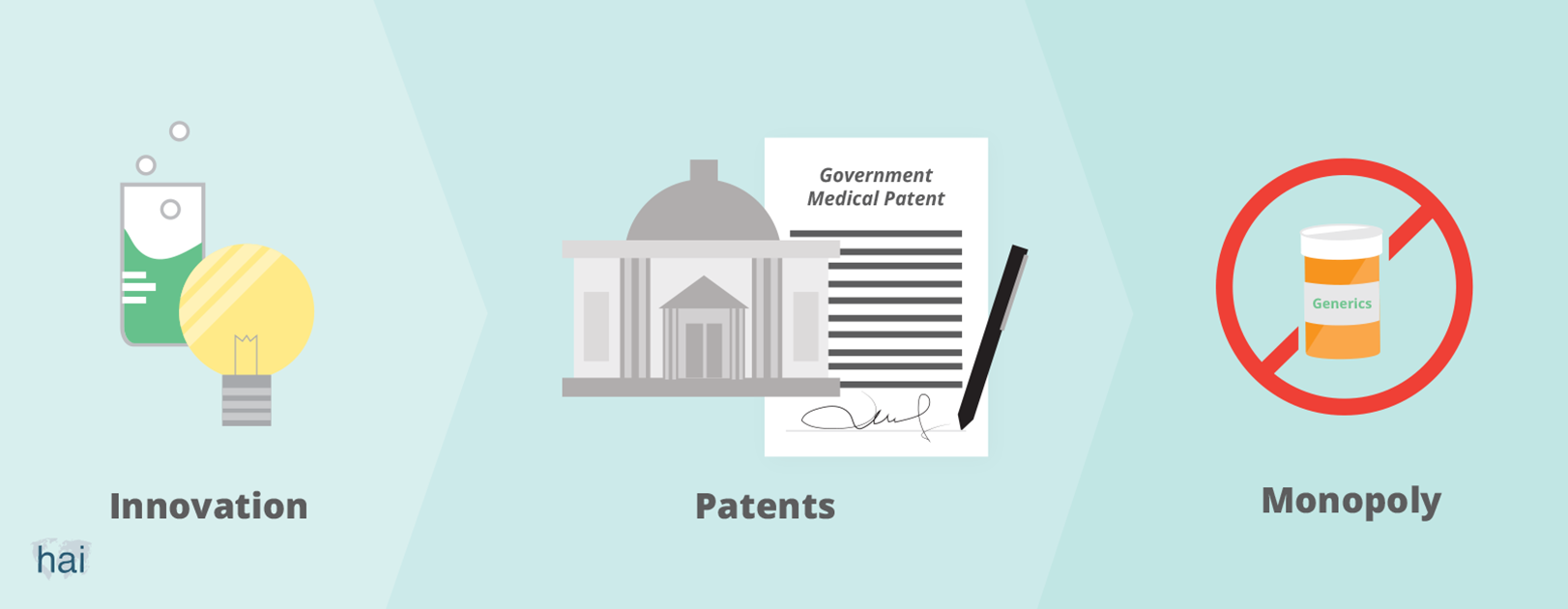

Governments grant patents to people who invent something useful. When you have a patent, you can prevent others from making, using, or selling your innovation for a certain period of time. The minimum length of a patent, which is set by the World Trade Organization, is 20 years. If you invent a new product, like a medicine, and obtain a patent for it, you will have the monopoly—or exclusive control—of the supply of, and sales for, that medicine in the market. Without competition from others, you can then ask a high price for your medicine.

The patent system is a social policy tool that is intended to encourage innovation. Governments grant innovators a patent as a reward for their innovations. Society, as a whole, would then benefit from these innovations.

Today’s system, particularly within the area of pharmaceutical innovation, is out of balance. It provides excessive (financial) rewards to patent holders (mostly large pharmaceutical companies) while creating huge costs to society. Those who cannot afford to pay for newly-innovated medicines are excluded from the benefits.

When you have a patent, you have a monopoly because no one else can bring the patented product to market. A company uses a monopoly to ask the highest possible price for its product. Usually, the monopoly price of a product has no relation to the cost of production. Take, for example, costs for sofosbuvir, a medicine that is part of a 12-week treatment for hepatitis C. Although the cost of producing the medicine is US$68–136, the company that holds the patent sells it for up to US$84,000.

A patent holder can stop the low-cost production of its medicine in any country where a patent has been granted for it. By doing so, the patent holder can dictate the price of the medicine.

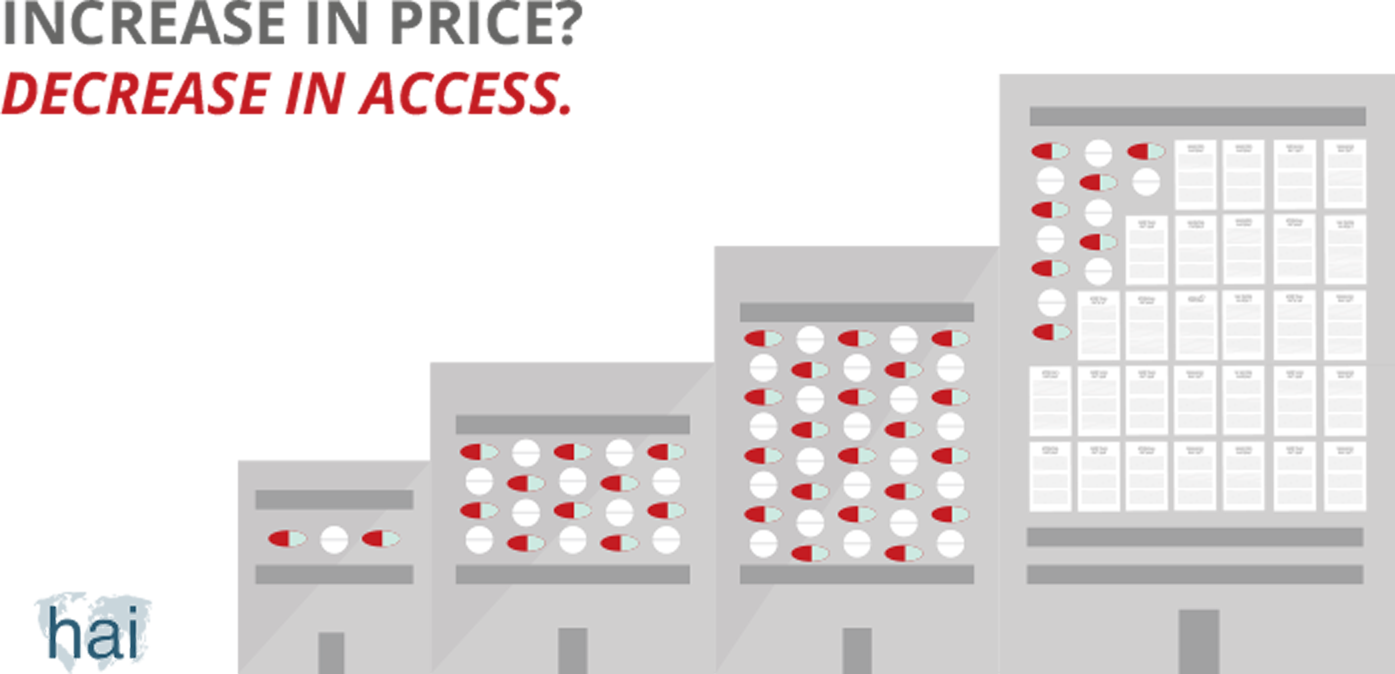

When no patent barriers exist, multiple generic producers can enter the market. When multiple producers market a product, market competition occurs. This competition drops the price of the medicine—sometimes very steeply—bringing it closer to the cost of production.

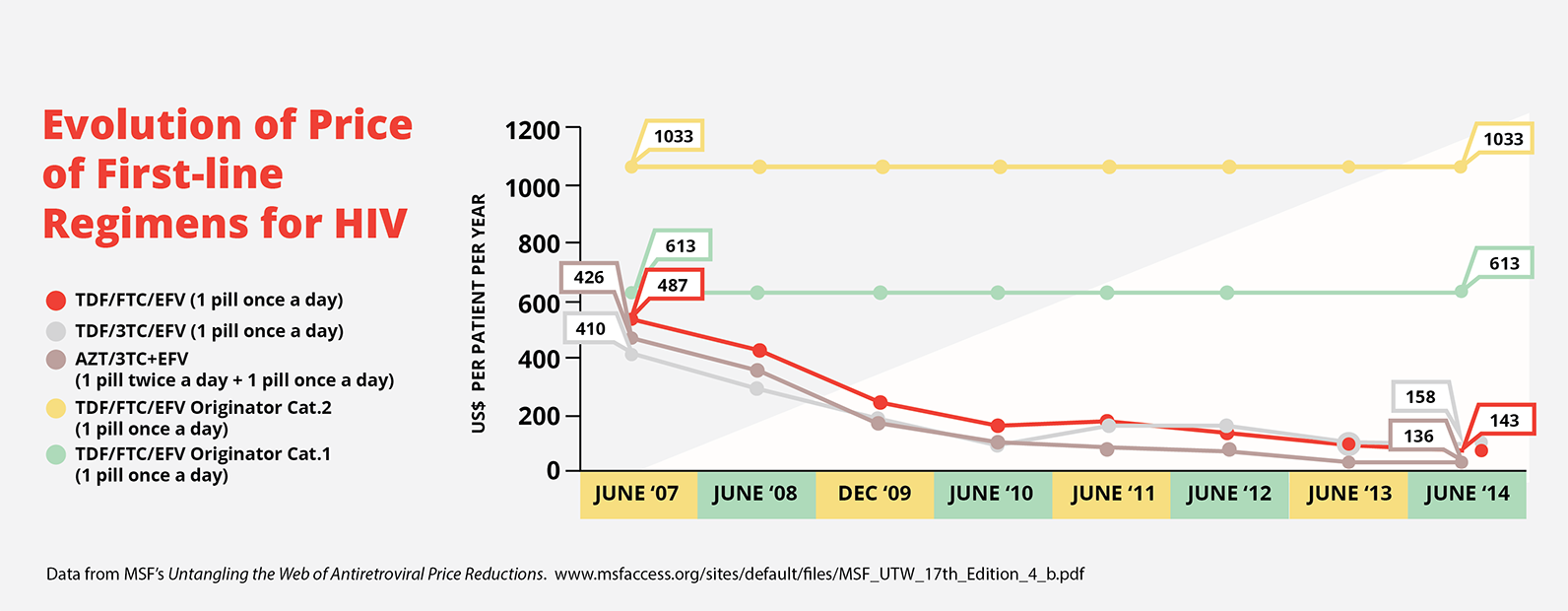

This occurred with the cost of first-line antiretrovirals, which are used to treat HIV. In 1999, the three drug cocktails to treat HIV cost US$10,000–15,000. Today, thanks to generic competition, these medicines are available for US$140. This graph shows how costs of generic versions of the triple drug treatment have come down over the years, while the branded product price remained the same.

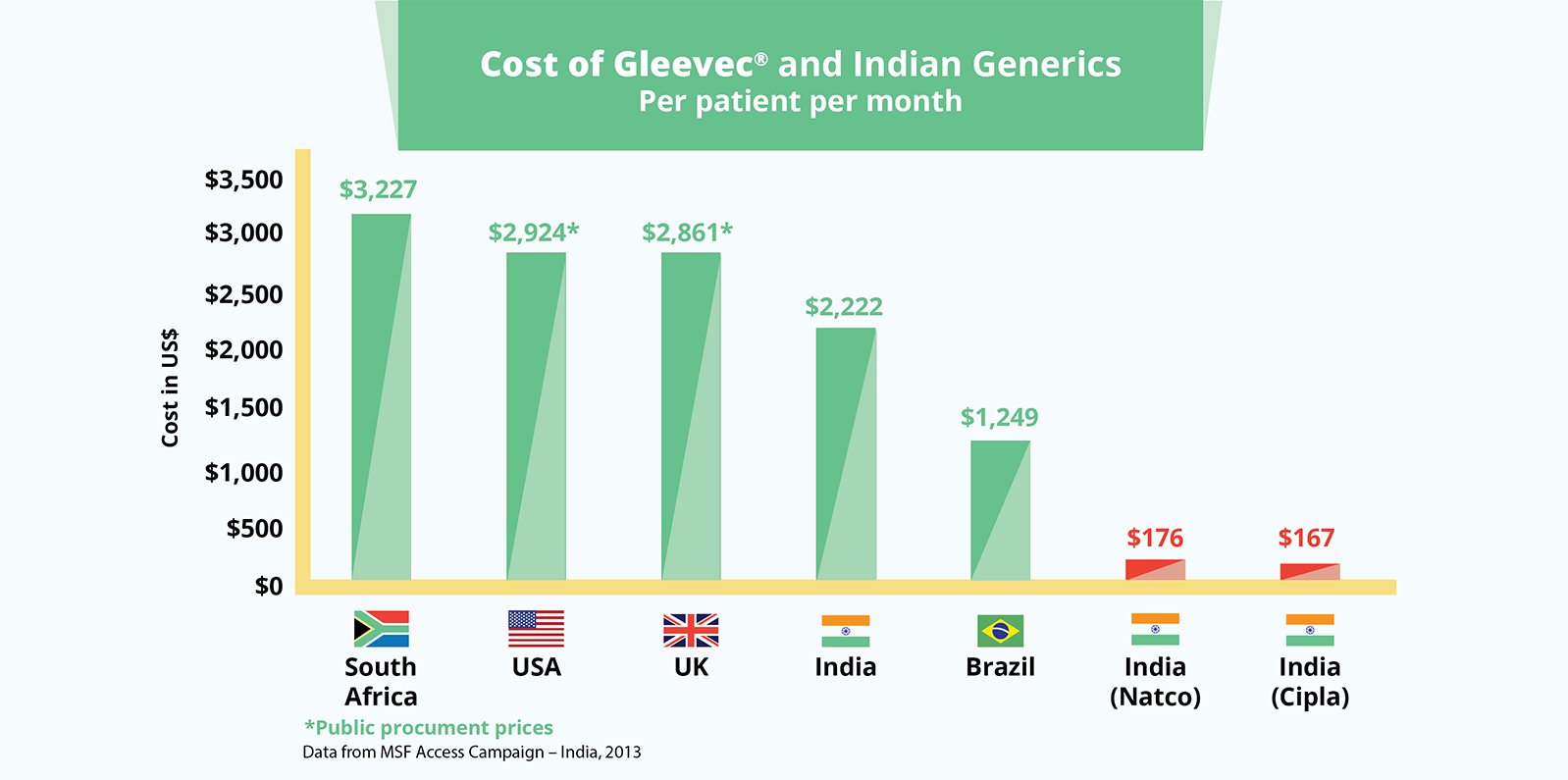

The cancer drug, Gleevec® (imatinib), also demonstrates the huge differences between a monopoly and generic price. South Africa pays over US$3,227 per patient per month for the branded product. In India, where the patent was not granted, the drug is priced at US$170 for a month’s treatment.

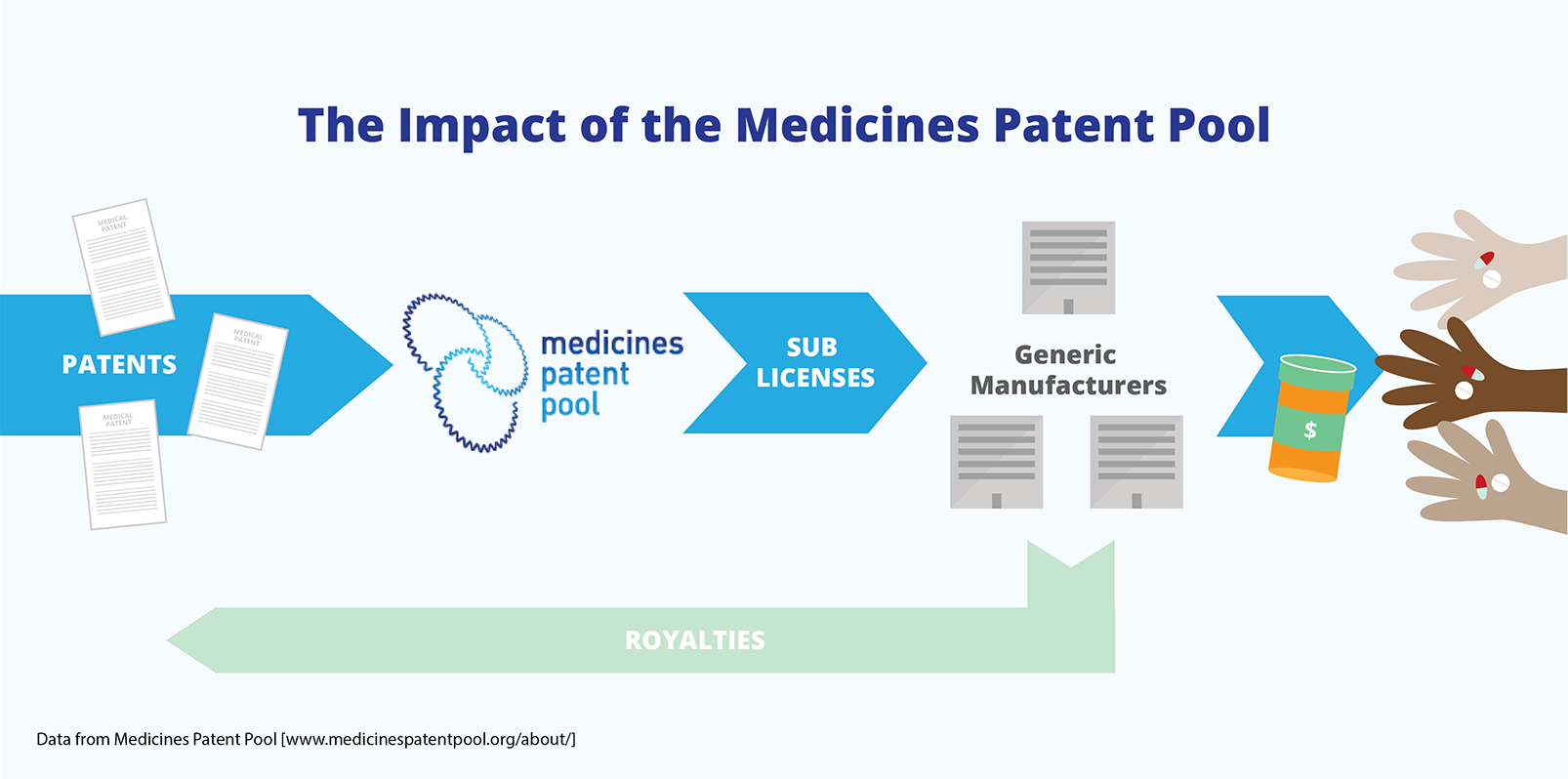

No. When you hold a patent, you can grant others the right to use it. This is called licensing or voluntary licensing. For example, when you have a patent on a medicine, you can grant another manufacturer, like a generic manufacturer, a licence to make it. Often the generic manufacturer (licensee) will agree to pay a royalty (an agreed percentage of the sales of the product) to the patent holder.

Licences that allow for the production of a medicine can be given to multiple generic companies. This creates a competitive market, even though a patent has been granted for the medicine. The Medicines Patent Pool, which was established in 2010, is an example of an international voluntary licensing mechanism. It ensures that licences for patents on AIDS medicines are available and that patents do not create barriers to access.

Governments (which grant patents) can also give others, besides the patent holder, the right to use a patent. This is called compulsory licensing because it does not require the agreement of the patent holder. In other words, if the patent holder refuses to give a voluntary licence for its product, the government can step in and grant licences. Royalties are often paid to the patent holder under compulsory licensing agreements.

The government can decide to grant a compulsory licence, including those for 'government use', for a variety of reasons. Some countries, under law, include 'high prices' of medicines, or a 'lack of access to medicines' as grounds for instituting compulsory licences. For example, French law authorises compulsory licences when medicines are “only available to the public in insufficient quantity or quality, or at abnormally high prices.”

Compulsory licences are granted on a country-by-country and case-by-case basis. Although they can bring down the price of medicines, a more structured solution is needed.

This is a very common misunderstanding and not true. If a government is faced with an emergency, it can issue a compulsory licence without first trying to seek a voluntary licence. This makes sense because negotiating a voluntary licence can take time and, in an emergency, there is no time to waste. A compulsory licence in an emergency situation has slightly easier rules, but an emergency is not a condition for issuing a compulsory licence. Governments are free to determine what constitutes an emergency situation. For example, many governments have referred to the HIV epidemic in their countries as an emergency situation and allowed the purchase and importation of generic medicines.

The Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) stipulates that products produced with a compulsory licence are “predominantly for the domestic market.” This, of course, has created problems for countries that rely on imports from other countries to satisfy their medicines needs. Such countries would not be able to make effective use of compulsory licensing because they lack the production capacity. Other countries may not be able to supply them because they can only export a ‘non-predominant’ part of the production under a compulsory licence.

The World Trade Organization recognised this weakness and, in 2003, adopted changes to TRIPS, which allows, under certain conditions, the production of generic medicines under a compulsory licence for export to countries that need access to such medicines. India, a very important producer of generic medicines, has a good provision in its law that implements this flexibility. If India receives a request for a generic medicine that is patented in India from a country that is not able to produce the product, the Indian authorities provide the necessary licence to the producer to make and export the medicine.

Who told you that? Since 1995, the rules of the World Trade Organization (WTO), the international body that regulates trade, determined that all countries must implement a patent system and provide patents for a minimum of 20 years. Before 1995, many countries did not grant patents for pharmaceuticals because they did not consider this to be in the best interest of the public. India, in particular, did not start granting patents for medicines until 2005. As a result, many AIDS medicines could be produced in India as generics.

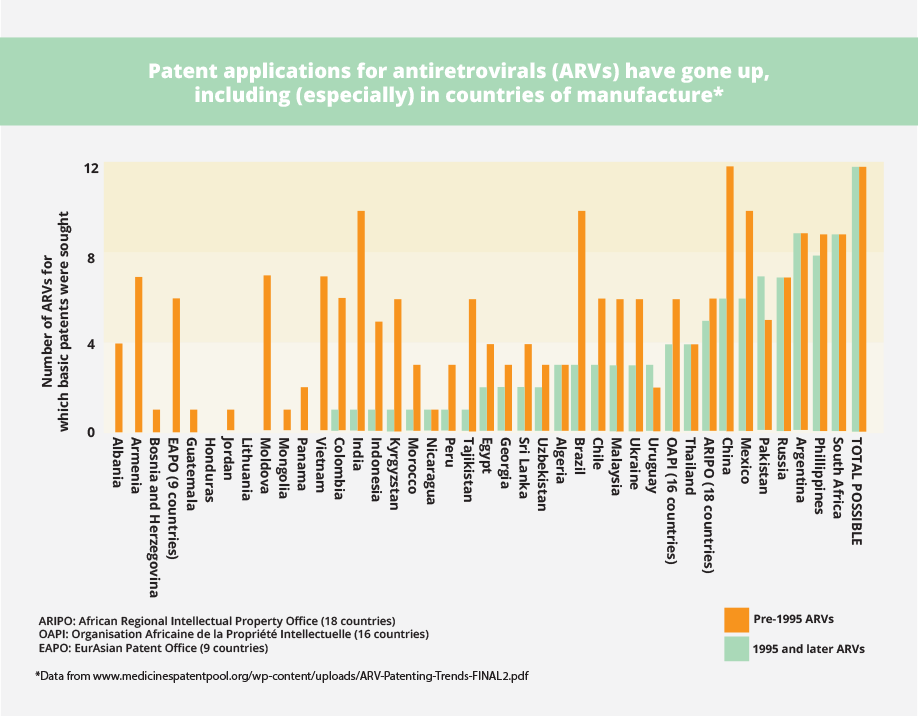

See, for example, what has happened with patents on AIDS medicines in developing countries before and after 1995. The increase in patents for medicines is particularly dramatic in countries with production capacity, such as India, Brazil, and China. This means that generic companies will not be able to produce low-cost versions of new patented medicines unless licences are available.

The least-developed country members of the WTO obtained the right, in 2001, to delay the granting of patents for pharmaceutical products until 2016. And since 2013, those countries can postpone the implementation of TRIPS entirely until 1 July, 2021. This only applies to 33 of the 159 WTO country members—and very few of them produce medicines. These countries will therefore need to continue relying on importation from other countries that now grant patents.

Patents are important for companies because they secure high profits. These high profits, however, do not secure the development of new medicines that are needed. The patent system provides incentives to bring to market products that can be sold to people who can pay the highest price.

Some companies are honest about this. For instance, the chief executive officer of Bayer, in response to a compulsory licence that was issued in India for his company’s cancer drug, Nexavar (sorafenib), said:

"Is this going to have a big effect on our business model? No, because we did not develop this product for the Indian market, let's be honest. I mean, you know, we developed this product for Western patients who can afford this product, quite honestly.”

Bayer was selling this drug for US$65,000 per patient per year. The average income in India, at the time, was US$3,840 per person per year. The price of the generic version of sorafenib was US$2,124.

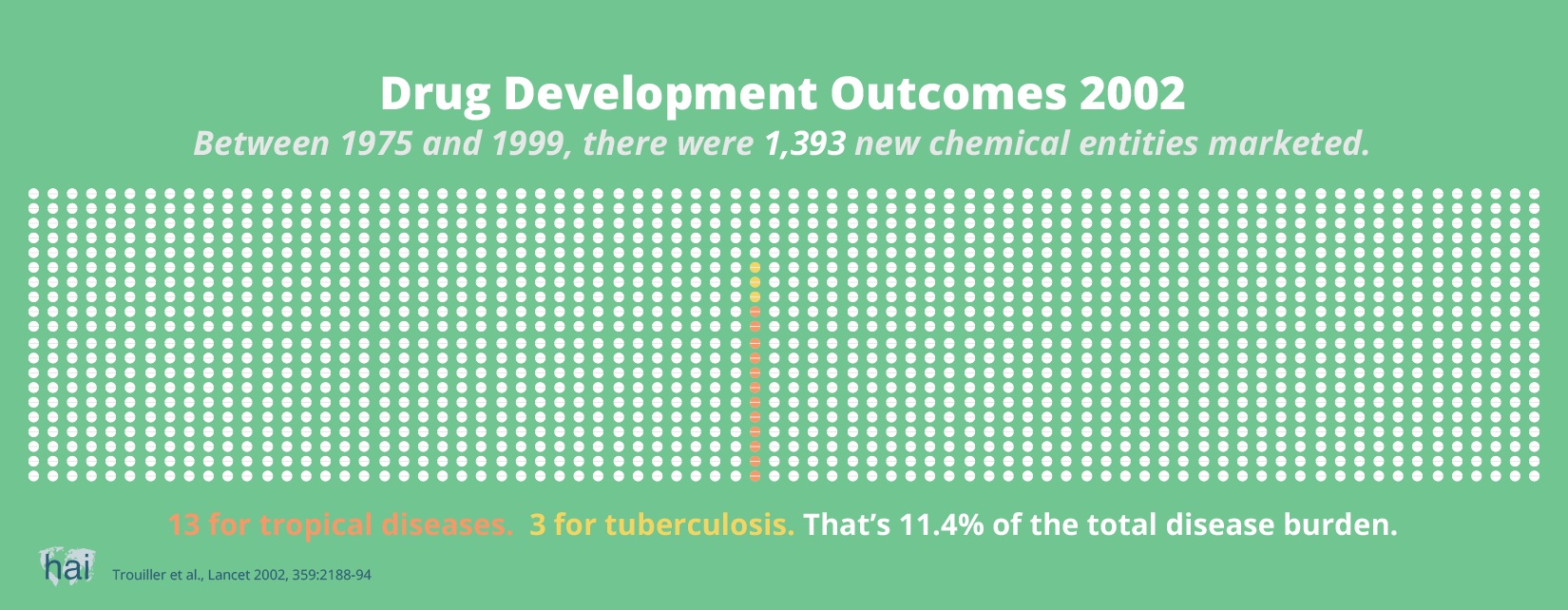

It is not profitable—and therefore not commercially interesting—for companies to invest in the development of medicines for poor people. As a result, many diseases are neglected by commercial companies, and medicines that are developed are priced out of reach of poor people.

A World Health Organization commission, which studied the impact of patents on public health, concluded:

“There is no evidence that the implementation of the TRIPS Agreement in developing countries will significantly boost R&D in pharmaceuticals on Type II and particularly Type III diseases. Insufficient market incentives are the decisive factor.”

Type II and III diseases refer to 'neglected diseases', which mostly or exclusively occur in poor populations and do not represent market opportunities for commercial companies. Despite the dramatic increase in the protection of medical patents in the last two decades, we have not seen a dramatic increase in the development of new treatments for neglected diseases.

Another major problem is the lack of investment by companies in the development of new antibiotics to address the current global antimicrobial resistance crisis. Few companies are investing in antibiotics R&D because they will not be able to sell them aggressively and at a high price.

So, it cannot be said that more patents lead to more innovation. If sufficient market prospects do not exist, no new drugs will be developed by commercial entities. And increasingly, globally available patents will further enable companies to charge the highest possible price.

While the availability of patents for medicines has also greatly expanded in wealthy countries, the level of innovation has not kept pace in the last three decades.

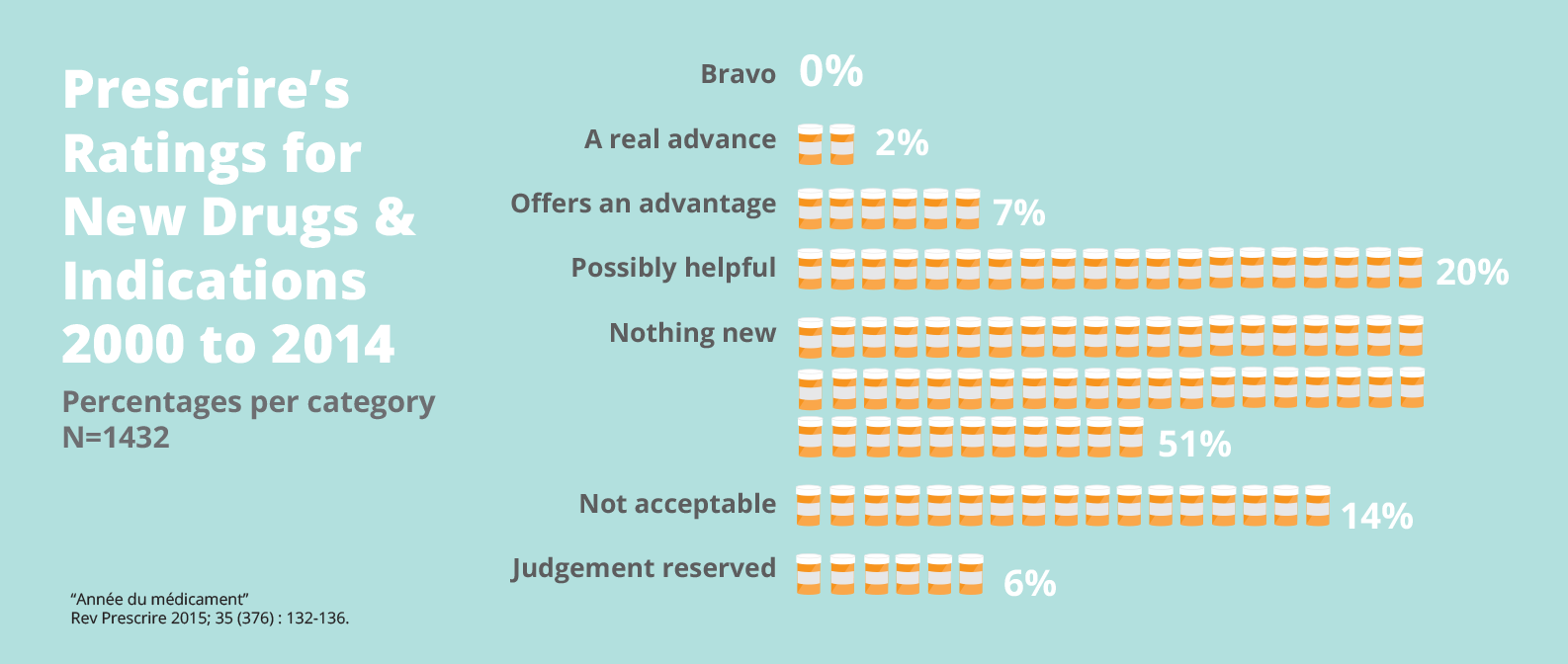

A 12-year analysis of 1,158 new drugs brought to market in Europe shows that only two percent offer a real advance over existing therapies. No real breakthroughs were recorded. And more than half were ‘nothing new’—mostly so-called ‘me-too’ products that aim to take a share of a competitor's market, but offer little or no additional therapeutic value for patients.

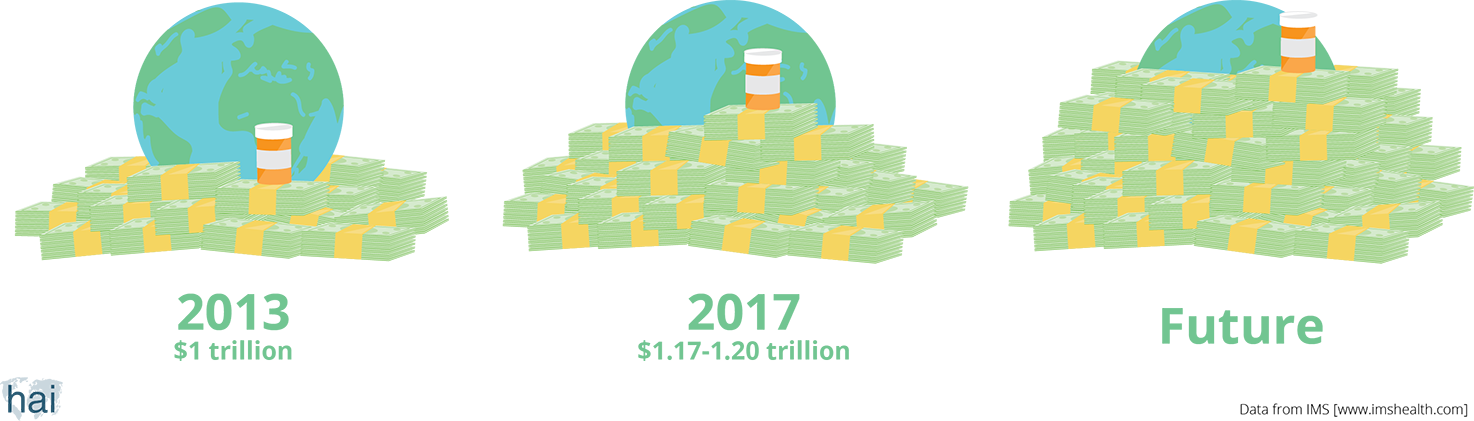

The size of the world pharmaceutical market in 2013 was US$1 trillion. This means that we, as consumers, have spent that amount of money on medicines in one year. The global pharmaceutical market is expected to grow. By 2017, people around the world will spend a total of US$1.17–1.20 trillion.

It depends who you ask. The lack of transparency around R&D costs is a massive problem. According to the pharmaceutical industry, it costs US$1.2–2.6 billion to bring a new medicine to market. But the Drugs for Neglected Diseases initiative (DNDi), a non-profit organisation that develops new medicines, says it costs much less—€100–150 million (approximately US$113–169 million), excluding in-kind contributions from partners. DNDi’s estimate is based on the actual costs for products that it has, or is, developing. Interestingly, although Novartis’ expenditure on the development of its cancer drug, Gleevec® (imatinib), is estimated to be US$38–96 million, it made a staggering US$4.675 billion in sales in 2012 (US$390 million per month).

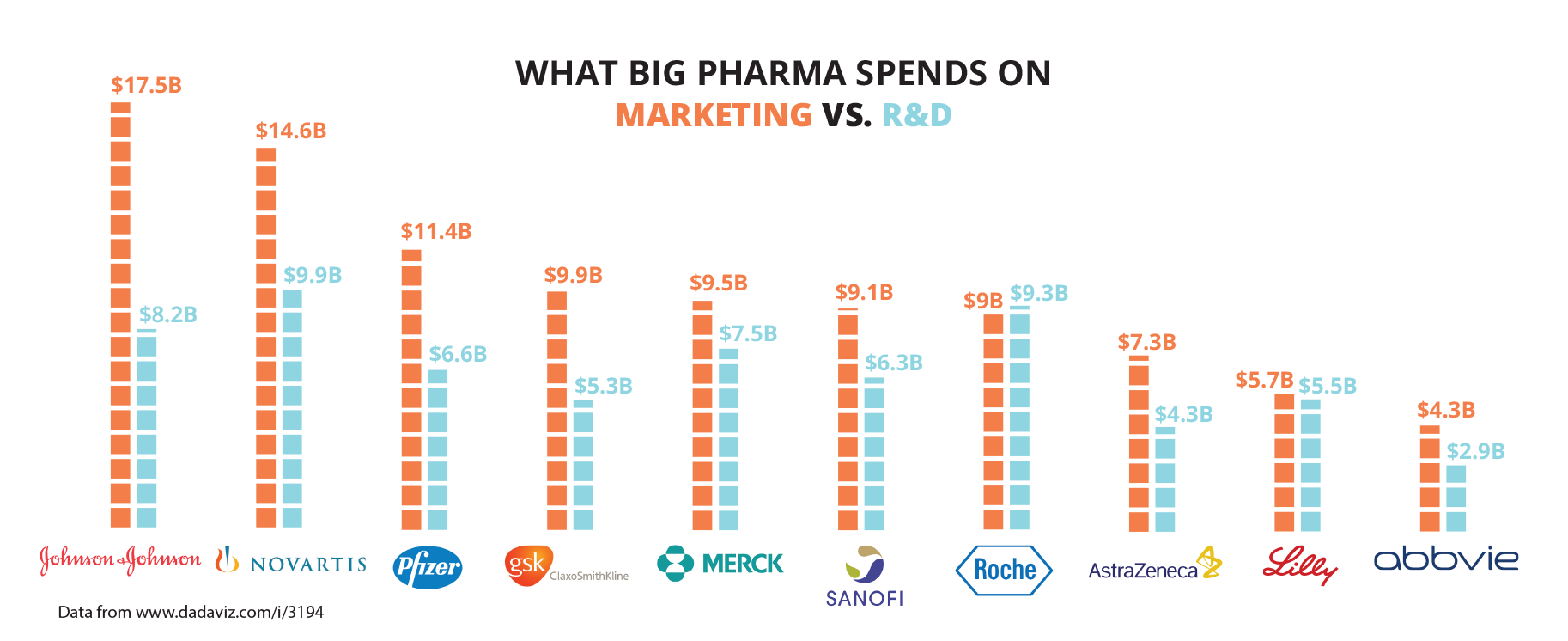

The global pharmaceutical and biotech R&D expenditure in 2013 was US$51.6 billion, according to the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America. Meanwhile, that same year, the pharmaceutical industry spent US$90 billion on marketing—twice its R&D expenditure.

You and me!

We all pay for the R&D of new medicines by buying medicines out-of-pocket, or through our health insurance, social security and/or taxes. Mostly, we pay through high drug prices.

Governments also contribute to the research cost of new medicines. A study of medicines approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) between 1990 and 2007 showed that, of all newly discovered drugs, 10 per cent were discovered through public sector research. But if one looks at the medicines that were eligible for ‘priority review’ by the FDA (meaning that they were of greater importance for health), the share of public sector review doubles to 20 percent. This also indicates that public sector research for new medicines has a greater impact for public health than the new medicines researched by the industry.

Shouldn’t governments demand more control over the money they spend on medicines?

Today, the main set of global rules shaping R&D is the 1994 World Trade Organization’s Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS), which requires countries to provide patent protection for medicines. Patents allow pharmaceutical firms, through their monopoly position in the market, to recoup their investments and make generous profits. This leads to high drug prices. Although all countries that purchase medicines contribute to the cost of R&D through TRIPS, an undesirable result is the rationing of medicines to people who can afford them and an exclusion of people who need them. It also leads to R&D priorities based on market prospects instead of health needs.

Pharmaceutical pricing by drug companies has become a race to the top. In the last decade, the prices of some cancer medicines, for example, have doubled. New treatments for hepatitis C cost US$65,000–100,000. For many people around the globe, the high price of medicines is a huge problem—and sometimes a matter of life and death. This, coupled with the lack of investment in the development of new products for important priority diseases, such as tropical diseases, as well as new antibiotics, means that it is time to develop new models to pay for the R&D of new medicines—models that will lead to medicines that are affordable and desperately needed.

One alternative model is ‘delinkage’, which means changing the relationship between the cost of R&D and the price of the product. With this model, large amounts of money (in the form of prize funds) would be available for innovators (institutes or corporations) that develop a needed new drug. Innovators would be rewarded based on the importance of the new medicine to the field of health. R&D would then be paid directly to the innovator and the product could go to market at a low price.